co-living – experimental township

Written By

Ellie Duffy

24.05.2022

What are you looking for as a judge of the 2022 Davidson Prize?

We’ve already completed the first round of judging and seeing the innovative approaches of the entries has been really exciting. What they clearly demonstrate is the prospect of far more nuanced and creative approaches to co-living in the very near future.

In that round, the longlisted entries champion important issues such as childcare and shared, communal responsibility for public realm and civic spaces. They also look at how to bring people of different genders, ages, abilities and ethnicities together in spaces that reflect diverse ways of sharing and collaborating. There were also some fascinating proposals to disrupt the ghettoisation of cultural groups and social class systems – to create more inclusive and resilient communities through architecture. I’m really looking forward to seeing how the finalist teams develop their ideas at the next stage of judging!

Is there an existing co-living project that particularly intrigues you?

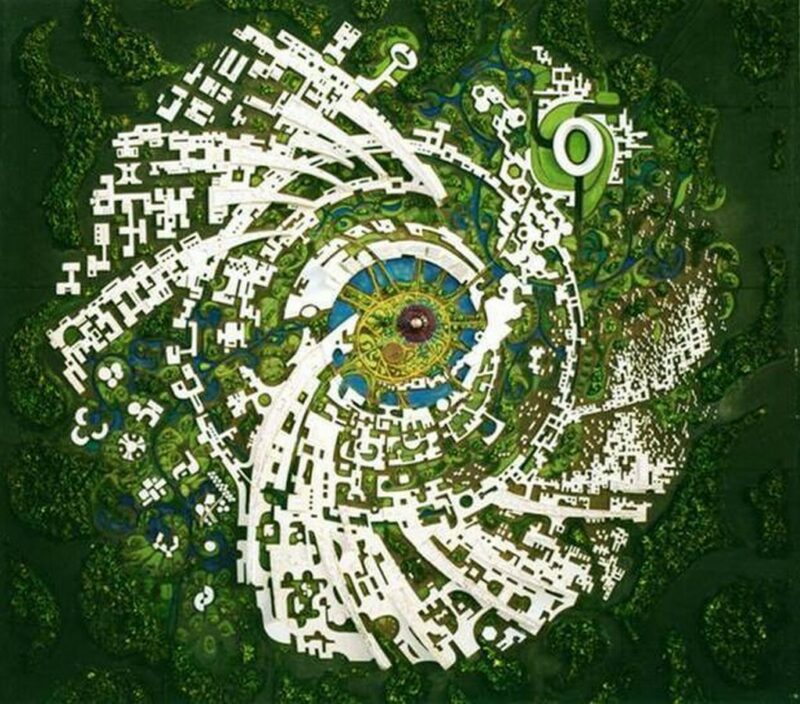

I’ve always been fascinated by Auroville, an experimental township near Pondicherry in South India. It was founded in 1968 as a reaction to the problems plaguing global cities at the time – pollution, corruption, traffic, urban sprawl and problematic social systems segregating people by class and caste. The town was designed as a collaboration between architect Roger Anger and its founder Mirra Alfassa, who was known as ‘The Mother’. There’s a temple dedicated to her at the town’s centre and the various zones that spiral out from it are dedicated to residential, industry, culture and education. People from all over the world came to settle in the utopian project, building their own homes and trading skills, knowledge and objects in a cashless society. Visitors pay a fee to come to stay, and this is collectively held to subsidise inhabitants in need. Auroville’s economy and social structures continue to evolve as part of the experiment, providing some interesting models that reflect contemporary concerns.

What are your personal experiences of shared living?

Living with others is necessary but not always easy, especially since housing isn’t always designed to accommodate different age groups, needs, ways of living or relationship structures. I’ve lived with others for most of my life – from family to friends, partners to initial strangers. I probably learnt most about co-living when I moved back to India with my mother and sister to live with my grandparents in the early 90s. Their house was designed by the late architect Charles Correa as a very open and convivial space, with a large orange front door that frequently pivoted open to welcome people for a chat, a drink or a party. There was always room for people to stay, and over the years the architecture proved accommodating to expected and unexpected changes as its inhabitants changed and aged.

More recently, like many people during lockdowns I got to know my neighbours better. I live in a mansion-block flat built in 1900, which shares a communal garden with a seemingly identical block opposite. The buildings are close enough that we can see the lives of our neighbours play out in detail. What was previously a casual source of interest and amusement became a lifeline of mutual support during Covid. Living alone, I suddenly had a network of communication that evolved into coffee mornings on the street, learning new lockdown skills through a knitting club in the garden, long walks in the local parks and so much laughter, advice and support.

Have you ever wanted to live in a commune?

I never thought so. But I did grow up living in flats and still enjoy living in close proximity to others, hearing life going on around me. I’m fascinated by system design and in this context that means how the chaos of living together actually enables a different kind of shared efficiency and collaboration. Through my architectural education and teaching career, I’ve researched some of the more extreme co-living experiments to try to understand where and why they fail. Examples include HI-SEAS – the Mars simulation in Hawaii – and Rajneeshpuram, which grew out of a spiritual movement in Pune, India to become a settlement that took over the town of Antelope in Oregon. Closer-to-home examples include property guardianships across the UK – an interesting model for how innovation and adaptation within a problematic and precarious system could in fact inform the evolution of greater rights, improved living conditions and different ways of affordable and collective living. So, I am perhaps more interested in communal living than I realised and maybe some form of co-living will be part of my future after all…

Would you say that its demand or supply that’s holding back the development of alternative models of living?

I’d say it’s the joint inability of societies, designers and developers to imagine alternative ways of living beyond the nuclear family. We need to also provide architecture that reflects alternative family models and allows for different kinds of relationships and forms of living – and this requires different financial models. The current provision of pocket living or co-living spaces is limited to specific incomes and age brackets – and there’s not enough focus on intergenerational living.

One goal of The Davidson Prize is to promote excellent communication of architectural ideas. Where do you see the communication of design heading?

I’ve long believed that architects need to be communicators at heart. At every stage, architecture requires collaboration and communication with a wide range of people – from users to engineers, builders to developers. Seeing increasing communication through time-based media and mixed reality now makes me hopeful that there’s a more speculative and creative future for architectural communication. I don’t think architects place enough value on our unique skills in communicating design, so it is great to see The Davidson Prize recognising the importance of this and showing its value in encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration. I’m really impressed by how the entries to the 2022 Prize have used different media to communicate their ideas – from diagrams to drawings to collage – and I can’t wait to see the films from the three finalists!

The Garden of Privatised Delights co-curated by Manijeh Verghese for the 2021 British Pavilion at the 17th International Architecture Exhibition at la Biennale di Venezia is on show at the Building Centre, London WC1 until 15 October 2022.