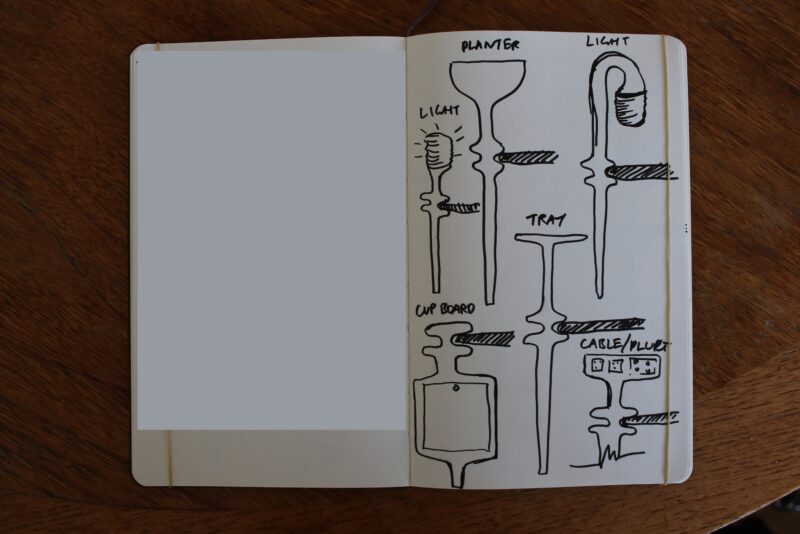

Sketch for a modular desk designed during lockdown. Credit: Heatherwick Studio

Now is the time to ask how shall we live

Written By

Amanda Baillieu

22.08.2020

Thomas Heatherwick is one of the UK’s most prominent designers and the founder of Heatherwick Studio whose projects include the Olympic Cauldron, the Routemaster Bus and Google’s new headquarters in King’s Cross. He is a judge of the 2021 Davidson Prize

How did you come to know Alan?

I was told Alan had invented a way of using computers to make visualisations that could captivate people and help communicate properly. He’d only been going a year or two and I went to see him in Chiswick. I had some budget to help with imagery but he talked me out of it. He said ‘just do a drawing yourself’ and I was dumbfounded. I’d just come out of college and I had a budget to pay somebody something and he was saying ‘no’.

But in a sense he was right. There is soulfulness to doing a hand drawing. That’s something I think we’re coming back to now.

So many designers have gone on this adventure of hyper-reality, and we’ve just got bored of that feel. It gives you the creeps. There’s something appropriate about hand drawing because it illustrates the reality – that you haven’t resolved everything yet.

You have always set great store by the need to communicate your ideas and connect with the public. Why?

I learnt how much it matters to engage others because how can you really expect anything to happen if you don’t?

I remember being invited along to the Architecture Foundation in the 1990s and I sat in on some of the conversations where the board, the friends and advisors of the Foundation were all saying how terribly architecture was communicated and asking, ‘how do we connect with the public?’ It seemed everywhere I turned there were these phenomenally clever people in this profession who weren’t actually putting their heart into trying to connect and engage with others.

So as a studio we’re trying to make places that are led by asking how would people actually feel when they’re there? Communication isn’t separate from design – it’s about trying to think of the right experiential story in the design.

Some of your best-known projects – from the UK Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo to Coal Drops Yard – are about bringing people together. Will placemaking survive the pandemic?

I think there’s an eternal thing about physically being together that we’ll never get around. But the crisis has pushed us in an interesting way, and this is one of the most challenging problems we’ve ever had to solve. But I do think we’ll come through this and find a way of coming back together.

But we are left with these broken assumptions that our society was based on: static models of retail, static models of work and static models of home. We’ve got away with creating places where people come because they’ve got to, because they have to work there, but now they have another option. You don’t have to go to a shop, you don’t have to go to a place of work, you can even experience museums three-dimensionally, sometimes at a higher resolution than if you were standing in front of the art work. If you've had that experience why would you go out, why would you go anywhere? So for me it’s an exciting time because it’s going to be about emotion.

How will the pandemic affect your studio if people want to shift to a blended work life?

For me the studio has got to become like a community centre or a cultural centre, or a temple of our values for people working from their bedrooms or dining tables. In a way I think our cities at a bigger scale will become that – a meeting place – because you’re not chained to the city anymore but it can give you culture and a chance to connect with people.

Turning to the theme of The Davidson Prize, do you think living and working could go on under the same roof?

I have experienced live-work. I had band saws, circular saws and welding equipment and I lived there and I missed it when I moved and the studio grew a bit and I lived in a conventional little house. It felt wrong. By pretending to balance life and work it created a polarisation – as if life was different to working. Both are joyous.

Spending three months at the same desk using video conferencing to communicate has challenged all of us. Our table design came out of this rethink because we craved nature and began to see the space around us as a mini-television studio – what is behind you and around you is now being seen by the world.

A year ago if someone had asked us to design a work desk we would have said no. But in lockdown it suddenly seemed relevant, and The Davidson Prize is extrapolating beyond the desk to the whole living space – and that’s exciting.

Modular desk designed during lockdown. Credit: Heatherwick Studio